33. Mongol Aspiration and Bilabialization

Such is the situation with the variations of the initial consonants connected with the process of aspiration and bilabialization in Tungus, so that in reference to this language the hypothesis of G. Ramstedt of the initial *φ and that of P. Pelliot of the initial *p cannot be accepted. In other languages the similar processes might have a place too. The fact of aspiration in the Mongol language is particularly interesting. With all possible reserves as to my competence in Mongol I will now point out some facts.

The present Mongol languages and Mongol written language bear some traces of formerly aspirated initial vowels. Yet the mediaeval dialects recorded possessed well-developed aspiration, which is also met with in some living dialects [86]. Some words with stabilized glottals, e.g., k, g, etc., seem to have come out of the previously practised aspiration. For safety's sake, it will perhaps be better to say that the «aspiration» and «gradual glottid» also h and x exist in Mongol dialects just as they exist in the Northern Tungus dialects, but they are unknown in the Mongol written language and in most of the living dialects. If we suppose, then, that the process of aspiration existed during the mediaeval ages, it might be confined only to a certain group of Mongol dialects about which we have some information, but the other dialects might have had no aspiration. Indeed, the number of groups speaking an aspirated or a nonaspirated dialect might vary greatly. At the present time, most of the Mongol groups know no strong aspiration which may be percepted as h and x, but the groups using the aspiration might have been more numerous than the nonaspirating during the Middle Ages. Therefore I think that it is perhaps mere anticipation to consider the initial h of the mediaeval Mongol as lost nowadays. The dialect laid down as the basis of the Mongol Writ., as well as some modern dialects, might have no aspiration at all, while other dialects might be affected by this phenomenon. If this is so, then the idea that the consonant has been lost is erroneous, and «genetically» h has nothing to do with the hypothetic initial bilabial tenuis.

Besides the occurrence of the initial b, corresponding to the aspiration or zero treated by P. Pelliot as doublets, there are some other facts which point to the existence of bilabialization in Mongol. In fact, P. Pelliot («Les Mots, etc.,» op. cit., p. 236) quotes the following three parallels from a Chinese document, a short dictionary recorded in the sixteenth century: funaga~hunagan (mediaeval)~ unagan — «the fox»; f'uni — huni (mediaeval) — unin (Buriat)—«smoke»; and fula'an~hula'an (mediaeval) ula'an—«red.» These parallels are not very convincing, perhaps, for the Chinese author might percept h as f. However, we have another series of facts; namely, the Shirongol dialect, which gives xunisi by the side of funisi—«the ash,» «fulyan,» etc. Thus these dialects possess f in the words with initial h and zero. P. Pelliot {id., p. 251) considers it, in view of maintaining G. Ramstedt's hypothesis, as a secondary phenomenon due to the alteration h→f, analogous to the Chinese dialects. Yet he points out that the initial f is met with in the words with the labialized vowels, i.e., let us add, as it is in the Southern Tungus language. If this is so, then it is probably not a secondary phenomenon in the sense of h→f, but it is a secondary phenomenon in the sense of the «bilabialization of vowels,» and in first-hand labialized ones. Indeed, f treated as a secondary phenomenon of the h→f type does not help in establishing the original initial labial tenuis [87].

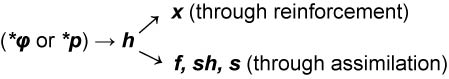

After the present work had already been handed over to the printers I received two publications concerning Mongol dialects which makes it necessary to insert this additional paragraph. A. Mostaert and A. de Smedt («Le Dialecte Monguor, etc.») this time treat of the phonetic system of the Monguor dialect of Kansu [88], in which one may observe both an aspiration and a bilabialization of vowels. In agreement with G. Ramstedt and P. Pelliot, these authors connect the phenomenon of «aspiration» disclosed in this dialect as a preservation of an archaic character of the Kansu dialect (op. cit., p. 146) and as a result of the alteration of the original «labiale fricative dure, ou, plus probablement l'occlusive dure *p» (op. cit., p. 804). The facts observed have inclined to make them recognize that f and x might have originated from «renforcement» and «assimilation» (op. cit., p. 805). It is interesting to note that side by side with this phenomenon one also meets with the initial sh in cases where we might expect to find glottal and labial consonants (ibid). The series under discussion may be thus represented according to A. Mostaert as shown in the scheme

One may also observe the loss of the initial vowel when it is not aspirated or bilabialized (op. cit., p. 807, § 21). Yet, in a great number of cases the initial voiced bilabial b is found voiceless and even an aspirated ph.[89] Moreover, there is a great number of cases when the initial x corresponds to the aspiration in mediaeval Mongol and zero in Mongol Writ.[90]

Cases in which the initial vowels are bilabialized are numerous. In most of them the initial f corresponds to h of the mediaeval and zero of the written Mongol, so that the tendency may be regarded as well established [91]. However, there are some cases where Monguor possesses at the same time parallel forms with zero and bilabializa-tion, with aspiration and bilabialization, as, for instance, in Goldi. In this respect, the analogy with Manchu (especially Manchu Sp.) is going so far that there are cases of parallelism of b and w, e.g., badzar~wadzar || basar (Writ.)—«the city»; bargu~wargu || bariku (Writ.)—«to take up»; and alternation w~j, e.g., withan~y'uthan || uitan (Writ.) || hiutan (mediaeval)—«narrow.» These cases are found parallel with zero in Monguor and aspiration in mediaeval, e. g., achi (Monguor) (Writ.) || hachi (mediaeval—«the grandson.» It may thus be pointed out that not only labialized vowels are increased with a consonant, but also the non-labialized vowels as well [92]. Another point of interest is one in the case of nonbilabialization where the initial vowel sometimes may disappear altogether; e.g., wese~ bese~jese || ebusun (Writ.), owosu (Urdus Sp.)—«grass.» This is a phenomenon which has been observed in the Tungus language [93]. The comparison of these phenomena as they are observed in the Mongol and the Tungus language leads us to the conclusion that the analogy is rather complete. It may be thus supposed that in Mongol the occurrence of bilabialization and aspiration is not due to the presence and degeneration of the initial labial consonant, but to the phonetic fashions of bilabialization and aspiration, which some time ago affected the southern Mongol.

Another publication is that by N. N. Poppe on the Dahur language, Xailar dialect. This dialect seems to show certain characters which support my thesis as well. N. N. Poppe has found the phenomenon of increase of the initial vowels with bilabialization {vide pp. 72, 73 of his vocabulary), and some traces of aspiration which he has not reproduced in his work. Another Dahur dialect, recorded by A. O. Ivanovskij, is strongly affected by aspiration, while bilabialization is little known [94]. N. N. Poppe makes a suggestion that the Dahur w and the Manchu v might originate from vowels (op. cit., p. 112) [95], yet he also suggests that w and v might have been preserved from the hypothetic initial *w, by analogy with the hypothetic initial *p. The phenomenon of bilabialization in the Dahur language seems to be quite recent [96], as it is also shown in Manchu Sp., where most of the labialized vowels and all the u's are supplied with w. Thus, in Dahur, as well as in Monguor, this process is still alive. The difference between the two languages is that the Monguor language also bears traces of an old process of bilabialization, while in the Dahur language it seems to be only of recent fashion.

If one does not presume the process of the loss of *p in the Mongol language, perhaps the whole situation would appear as simple as it is in Tungus; namely, that there existed, and still exists in some dialects, a tendency of bilabialization and in other dialects a tendency of aspiration, while some third dialects remained beyond these phonetic «fashions.» The southern Tungus (the Nuichen) and the southern Mongol (perhaps the Toba, and as preserved in Kansu) were long ago affected by bilabialization, while some Northern Tungus and some northern Mongol dialects were affected by aspiration (prior to the first records of the mediaeval Mongol; cf., also, variations of these phenomena in Tungus connected with the migratory waves, which, under a certain probability, may be connected with definite historic moments). Both phenomena might or might not be synchronous, and there might be no connexion between them. As I have already supposed, the fashion of bilabialization might originate under Chinese influence, or even under the influences coming from Central Asia. This fashion still persists in Dahur and Manchu Sp. supported chiefly by Chinese influence.

The Dahur language, considered in the light of this interpretation, appears to be recently affected by bilabialization and formerly to have been strongly affected by aspiration, while the Monguor dialect was strongly affected by both; yet the dialects which led to the basis of the Mongol written language were not affected by these phonetic fashions.

In my earlier paper (»Notes on the Bilabialization and Aspiration in the Tungus Languages,» written in 1927) I hesitated more than at present as to the possibility of generalizing my hypothesis concerning the phenomenon of bilabialization and aspiration in Mongol. The new facts expounded above dissipate my hesitation as to spreading my hypothesis, which I am now inclined to consider as a theory.

86. The existence of aspiration in Mongol is a well-known fact. So A. Bobrovnikov («Grammar of the Mongolo-Kalmuk Language») and A. Pozdneev (Introduction, p. viii) pointed out that the initial vowels as a rule are aspirated. G. Ramstedt («Comparative Phonetics of the Mongol Written and Xalxa-Urga Dialect,» Sec. 46, p. 44) treats this phenomenon in the Urga dialect as a «gradual glottid» (cf. Sievers, Grundziige, etc., fifth ed., 1901. Sec. 3S9), and N. N. Poppe («Mongol Names of the Animals in X. Kasvini's Work,» p. 205) repeats it in reference to the mediaeval Mongol words. However, this «gradual glottid» is so strong in some Western groups and in Dahur that in the records it appears as x. G. Ramstedt, in his later publication («Ein anlantender, etc.,» op. cit.), supposes that the h of the mediaeval Mongol languages, according to Yuan Chao Mi Shi (a.d. 1241) and as recorded by Guiragos, must be «eine damalige entwicklungstufe des ehemaligen P' od. f— lautes» (id., p. 8). W. L. Kotwicz treats it (Rocznik Orjentalistyczny, op. cit, Vol. II, p. 247) as an aspiration met with in the mediaeval Mongol groups, of which groups speaking the Amdo dialect and their neighbours have been produced. He compares it with the aspiration met with in Dahur. P. Pelliot («Les Mots, etc.,» op. cit.) designates it in the mediaeval Mongol as an aspiration h which is lacking in the present Mongol.

87. P. Pelliot seems to believe that the only way to prove the appearance of the initial h is to show its derivation from a labial, for he says that otherwise its origin would be mysterious. As shown, its origin is not mysterious at all, at least in the Tungus. The fashion of bilabialization might affect both the Tungus (Southern) and the Mongol.

88. A. Mostaert previously published his investigation of the Urdus (South) Mongol dialect, which is free from the aspiration and the bilabialization of the initial vowels.

89. E. g., in Mongol Writ. bichig, burkan, burgiraku, bokeiku, lurchag, belege, and bukuli are found in Monguor with the initial ph. This is not a general phenomenon, however, as it is also observed in Manchu Sp.

90. Most of the cases where the initial vowels are aspirated correspond to the words with the initial a and e of the Mongol Writ. However, there are also cases where the initial o and u are aspirated, e.g., oriyaku, ombaku, okor, and urum, are aspirated in Monguor.

91. Some of these cases are particularly interesting. There are some monosyllabic words, e. g., fan (Monguor) — on (Writ.) — hon (mediaeval)—«the year» (op. cit., p. 151) fe (Monguor) — oi (Writ.) — hoi (mediaeval) — «the forest» (op. cit., p. 155). Some of them have already been treated in the present work, e.g., for (Monguor) — egur (Writ.—he'Ur (mediaeval)—«the nest» (op. dr., p. 810) (cf. 'fir of the Urdus S. and infra, Chapter V); f'uda (Monguor) — uguta (Writ.) — huguta (mediaeval) — «the bag,» «sack» (cf. infra, Chapter V). A. Mostaert's transcription here and further is given in slightly simplified form.

92. The above quoted withan may be regarded as a case of the loss of the vowel u. The situation is complicated, however, by the fact that sometimes the vowels, like o and oe, are not labialized at all (cf. A. D. Rudnev, «Xori-Buriat Dialect,» op. cit., p. 11). What kind of vowels were originally found in the words where the initial vowels are now found to be «bilabialized» is not always ascertainable.

93. Cf. supra. Section 31; also »Notes on the Bilabialization and Aspiration in the Tungus Languages.»

94. In the series of «bilabialized» cases may be included the following words given by A. O. Ivanovskii vantabei || untaxu (Writ.) — «to sleep»; vaire || oira (Writ) — «near»; wakar || oxor (Writ.), axar (Kalm.) — «short»: also perhaps some more cases may be classed in this group. However, these cases are not so numerous as they are in the Manchu and the Monguor dialect.

95. Indeed, the word uas (Dahur), vasa (Manchu), as shown, is Chinese (cf. infra. Section 47). The same is perhaps true of another instance which he gives; namely, woa (Dahur), va (Manchu) — «the smell» (cf. «Notes on the Bilabialization and Aspiration in the Tungus Languages»). In «Notes on the Bilabialization and Aspiration in the Tungus Languages,» I gave several other instances which show that w and v are merely particular cases of bilabialization.

96. The recentness of this phenomenon in the Dahur language (in the Xailar dialect and also in the dialect recorded by A. O. Ivanovskij) is especially evident, for this language still behaves like nonbilabializing in the case of foreign words with the initial f. In fact, the latter is not always correctly reproduced, being altered into p. So two cases are reproduced in N. N. Poppe's vocabulary [faida (Manchu) and fan-se (Chinese)], and a case in A. O. Ivanovskij's [f (Manchu) = bi (Chinese)]. However, the initial f is sometimes correctly reproduced by the Dahurs [e.g., Manchu, fanchambi, fi, fulxu; Chinese, fuzen, according to A. O. Ivanovskij; Manchu, fafula, fur dan, according to N. N. Poppe]. This phenomenon is analogous to what I have observed in the Bir. dialect, including the fact that both the Tungus and the Dahurs pronounce correctly when familiar with Manchu. The behaviour of some Goldi dialects is the same.